Explore! each body wakes up on a wave

each body wakes up on a wave, is a multisensory art exhibition exploring the complex legacies of indentured diaspora by Rudy Kanyhe & Lauren La Rose with Aurélie Chan Hon Sen, Ines Gradot, Sabe Lewellyn, Natasha Soobramanien & Luke Williams.

Disabled artists and curators, Rudy Kanhye and Lauren La Rose, experiment with interactive print based artworks, and ways to build solidarity through critical thinking, reflection and play.

Exhibition Runs 07 June - 27 July 2024 at Glasgow Print Studio as part of Glasgow International Festival of Contemporary Art 2024.

each body wakes up on a wave, Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

For Glasgow International Festival of Contemporary Art, Glasgow Print Studio is delighted to present each body wakes up on a wave, bringing together artists using diverse print and printmaking techniques to address themes of empire, migration and transcultural solidarity.

Curated by artists Rudy Kanhye and Lauren La Rose, the exhibition intertwines new artwork, archival visuals, innovative textile installations, and photographs sourced from archives and libraries in Mauritius and the UK.

As disabled artists, educators and curators, Rudy and Lauren are interested in alternative ways of learning and how diverse audiences position themselves in relation to complex histories. The exhibition serves as a series of starting points to look critically at Scotland’s dark colonial past while subverting eurocentric narratives of colonial legacies of what these histories are supposed to look like.

Their curatorial approach is influenced by crip methodologies and the concept of creole.The title of the exhibition is inspired by the writings of Mauritian author Khal Torabully and his concept of coolitude, which emerged from his poetic exploration of indentured labour in works such as Cale d’Etoiles: Coolitude (1992) and Chair Corail: Fragments Coolies (1999). Originally, coolitude sought to humanise the Indian indentured labourers and their descendants. However, coolitude has now evolved into a universal philosophy that embraces the term "coolie" as a way to connect with geographical and cultural migrants across the globe.

Identity in diaspora is therefore not static or fixed, but subject to the continuous play of history, culture and power. This process known as creolisation, uniquely critiques multicultural approaches to nation building and diversity. Instead it offers an “uprooted” idea of mixed race (méttissage) identity and the recovery of occulted histories, in which bodies, languages and imaginations mingle in a constant transformation of difference. By connecting with the unsettled memories of colonial diaspora, including the ongoing impact of racism and imperialism, this exhibition asks how do we create radical decolonial spaces, and new forms of transnational solidarity, for disabled and marginalised bodies?

Working with Glasgow Print Studio has allowed Rudy and Lauren to experiment with new print based techniques, including the use of thermogenic inks, and ways in which printmaking has historically been used to both suppress and subvert complex histories. The term indenture comes from this history, to “indent” or to make multiple copies which correlate to each other, which was a technology used by the British government to track indentured labourers for over hundred years. Inspired by their recent research trip to Mauritius, Rudy and Lauren focused on creating a “way in” into a very serious subject, in a warm setting which relaxes people into a state of being able to engage, learn, reflect and dismantle unjust legacies.

Building on Rudy’s lived experience, the exhibition further delves into the collective memories of individuals who embody migrant communities, shedding light on diverse geopolitical narratives, systems of labour and untold alternative economies built by underrepresented women and their resonance within the broader experiences of diasporic individuals. each body wakes up on a wave, serves as a testament to the immense power of art to challenge and enhance our understanding of contemporary life. The words of Khal Torabully, “art liberates what the archives obliterate”.

each body wakes us on a wave, supports a Free Palestine and believes in dismantling imperial tools of oppression worldwide. Special thanks to our partners, Aapravasi Ghat Trust, Blue Penny Museum, CHARTS, Creative Scotland, Glasgow Print Studio, Glasgow International, Mahatma Gandhi Institute, National Library of Mauritius and We Are Here Scotland.

Explore! each body wakes up on a wave, Gallery Tour with Lauren La Rose

Below, I invite you to join Lauren as your guide through their new interactive exhibition at Glasgow Print Studio. To access the exhibition online please click here.

Recorded and transcribed by Naomi Brown and Kerry Douglas at Glasgow Print Studio Friday 31 May 2024.

Trigger warning, references to slavery, indentured labour, colonialism and injustice.

each body wakes up on wave, Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

We'll begin here, as most people will enter the space from this point.

Rudy and I are partners and collaborators, and we've been developing this research practice-led project. We're specifically researching what happened after the abolition of intercontinental, chattel slavery, particularly in Mauritius. Slavery was abolished in 1834, and according to history books, the British government faced the challenge of needing a workforce to continue the industrialisation of goods like sugar.

They came up with the Great Experiment, which was meant to prove that free labour was better than paid labour. This led to the creation of a new system of labour, distinct from slavery, based on a contract system which we still use today. It was based on the formation of the first nationalised immigration service. Before the abolition of slavery, the transport of workers was privatised (individual companies and plantation holders paid for the transportation of workers and this was very costly, making it almost unprofitable).

This led to what is known as indentured immigration. Mauritius was the first place where this was tested in 1834. Labourers from India were brought to Mauritius to work on sugar plantations, replacing formerly enslaved people. This started a global phenomenon of workers being transported across the Global South from Asia, Africa, India, and the Caribbean.....

However, the reality was that the British government tested the Great Experiment by transporting workers to Mauritius even before slavery was abolished. The first indentured immigrants in Mauritius were Chinese, brought during the time of slavery and living under similar conditions as enslaved people. A lot of them went back after seeing the conditions they were to live and work in. This is a contentious topic, but it's important to note that slavery and indentured labour are two distinct systems of labour, despite many interconnections. Some indentured labourers were tricked into the contract system or forced to work, especially in the first wave of indentured immigration. For others, indentured labour, despite its injustices, was a way to improve their lives, especially during times of war and famine.

Rudy’s ancestors came in the second wave of indentured immigration from India. The narrative of indentured labour is complex and nuanced. For this exhibition, we aimed to create starting points for discourse rather than presenting definitive research findings.

Dodo-Raphus-Cucullatus, 2023 Digital print. Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

Here, we have a digital print made at the Glasgow Print Studio by Rudy for Edinburgh Art Festival 2023. Rudy often uses archival materials and collage. This print includes stamps and money, which are considered the first archives of colonialism, representing different kinds of economy. Together we created collages using photographs we took in Mauritius, combined with archival materials.

In February 2024, we were fortunate to visit Mauritius for a period of funded research working with the Aapravasi Ghat Trust. The Aapravasi Ghat in Port Louis is a former sugar warehouse built by formerly enslaved people, and later used as an immigration depot for indentured immigrants. This site was crucial in processing indentured immigrants arriving in Mauritius, except for those quarantined due to cholera or disease. For example, if you had cholera you were sent to an island off the north coast, most of those people never made it to Mauritius including British soldiers.

We are deeply interested in creating an exhibition that serves as a starting point for discourse. We collaborated with the heritage curator, Vikram Mugon, to achieve this goal, bringing together a diverse group of people from different fields. We engaged with historians, heritage experts, archivists, and members of distinct communities.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, half a million people emigrated from India to Mauritius, coming from all across India. This means the community comprises individuals of different castes, religions, and languages, making it very diverse.

Our exhibition aims to use different types of material, including archival resources and our own experiences, to encourage people to think critically about their positions in relation to these complex histories. We hope to draw out specific connections between Mauritius and Scotland, fostering a deeper understanding of their intertwined pasts.

Being in Merchant City is particularly significant because this area is closely connected to Scotland’s history of colonialism and slavery. Merchant City is situated next to the river Clyde, where many colonial ships were built in Scotland, especially in Glasgow and Dundee. Specifically, ships like the Forth and the Clyde, which were constructed in Scotland, were used to transport indentured immigrants and sugar.

This creates a direct connection between ports, linked by water. We aimed to engage the audience here by highlighting these connections.Over here, we have thermochromic prints—one red and one purple—that further explore these themes.

The two thermochromic prints represent distinct architectural styles in Mauritius. One print shows Creole Colonial architecture inspired by the Southern United States, photographed at the Pamplemousse Royal Botanic Garden, which is the oldest botanic garden in the Global South.

This area used to be a French estate owned by what they call "planters'' in Mauritius or plantation owners. The architecture of these estates was inspired by the southern United States. These grand plantations featured expensive driveways, often referred to as "power avenues," which were meant to display wealth and status.

TOUCH! Creole Architecture en Rouge, 2024 and TOUCH! Creole Architecture en Violet, 2024. Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

The architecture includes large verandas, which are particularly interesting. In Mauritius, verandas were not just a feature of the house but a way of living, especially in the Victorian era when it was common to sit outside. Considering the hot and tropical climate of Mauritius, it's fascinating to imagine how British settlers adapted to this environment. The literature from that time often romanticised these verandas, drawing parallels between them and the decks of ships, evoking a sense of being transported to another place.

Second print. This distinct type of architecture is also seen in structures across many indentured sites. These buildings, likely constructed by enslaved people, were made with old stones. In our exhibition, we encourage people to engage with these structures by touching them.

We were initially conflicted about how to use the thermochromic ink in these prints. In our first attempt, touching the print caused the image to disappear. However, we decided against making these histories vanish. Instead, we focused on what happens when people get close and interact with the prints, revealing more of the image and thus activating and revealing history. This interaction is crucial to understanding and connecting with the past. And that and also that the more that people touch it, it changes the image.

Touch! Creole Architecture en Rouge, 2024. Action shot (Photo by Eoin Carey)

The vagrant house, also known as the immigration depot, was used to house indentured labourers and later imprison them. They serve as a stark symbol connecting the attitudes towards indentured labour to those of slavery. For instance, even though indentured workers had contracts and were paid wages, if they failed to show up for work due to illness or any other reason, they were treated as if they were shirking their duties and could be imprisoned.

This system reveals the persistent biases and attitudes from the era of slavery. We came across some unsettling literature from newspapers in the 1830s, around the time slavery was abolished. Plantation owners expressed confusion and frustration, saying things like, "We freed all the slaves, but they don’t want to come to work anymore." This reaction is eerily reminiscent of contemporary issues, reflecting an enduring misunderstanding of freedom and labour rights.

This historical attitude is strangely familiar, echoing sentiments we still encounter today about people’s unwillingness to take on multiple jobs or work under poor conditions. It’s a troubling and thought-provoking connection that shows how deeply these biases are ingrained and persist over time.

PLAY! Sugar Cane Ping Pong, 2024 screenprint, reinforced cardboard, sugar cane from indentured heritage sites in Mauritius, pampas grass, Installation view (Photo by Eoin Carey)

This piece incorporates sugar cane from an indentured immigration site, though the site's story is quite complex. Rudy's father owns a plot of land in Mauritius that has been passed down through generations since his ancestor, who was an indentured immigrant. The British government’s approach to indentured immigration was a calculated attempt to move away from the system of slavery while still maintaining a productive workforce.

Indentured immigration can be seen as a kind of public relations effort. Workers were photographed on the decks of ships rather than in the cargo holds to present a more humane image. They were also provided with healthcare to ensure their efficiency as labourers. The shift from slavery to indentured labour was largely driven by the need for a consistent workforce for industrial crops like sugar, which were crucial for the economy.

After slavery was abolished, plantation owners in Mauritius argued to the British government that they simply needed workers to continue their operations. This led to the consolidation of many small, independent sugar plantations into larger estates, which required more labour than before.

To make indentured labour more sustainable and less costly, the British government allowed workers to bring their families, religions, and cultures with them. This policy had a profound impact on Mauritius, enriching its cultural landscape and making food a significant cultural element. The relationship between labour and cultural production in

Mauritius is fascinating; it shows how labour influences culture rather than the other way around.

A notable policy change, known as the Morcellement Law, encouraged indentured immigrants to buy back unprofitable parts of the plantations. In the 19th century, the Indian indentured community in Mauritius collectively spent about ₹20 million rupees buying back land. This land acquisition significantly shifted the socio-political dynamics of contemporary Mauritius.

This piece aims to explore these legacies through a playful and interactive approach. By inviting people to engage with the work, we hope to highlight the enduring impact of labour on culture and history. Feel free to interact with it and reflect on its significance.

Bask in the Light of Freedom, 2024 Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

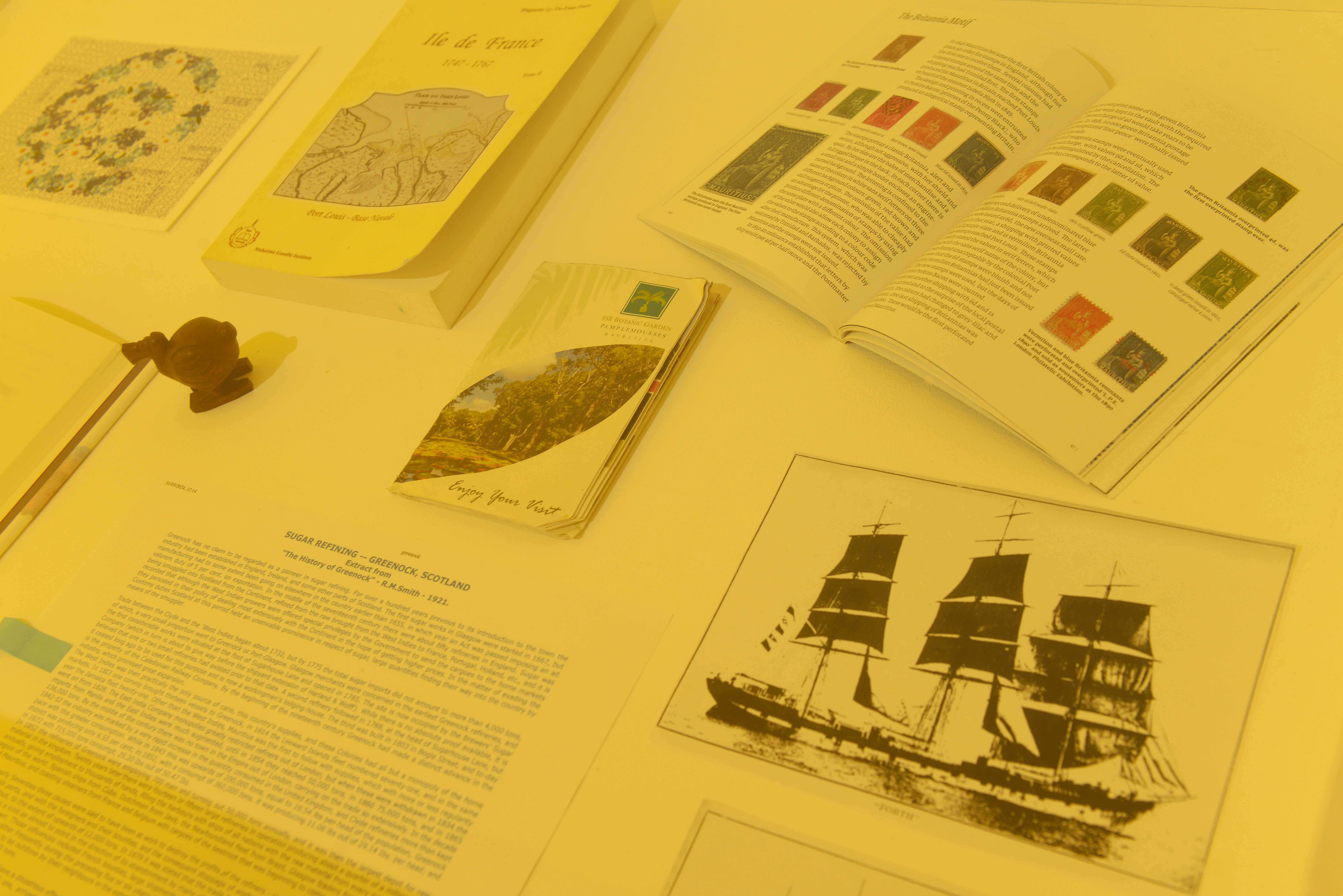

In the yellow room here, we will be presenting some of the research from our trip to Mauritius. The choice of yellow is inspired by the Mauritius independence movement. The national flag of Mauritius features four colours: blue representing the Indian Ocean, green symbolising the land, red signifying the struggle for freedom, and yellow reflecting the sun. Specifically, the yellow represents basking in the light of freedom. We aimed to create a reflective space bathed in this yellow glow to encourage contemplation of our research and the ideas from the independence movement.

Mauritius became a republic in1968. Although often described as having the most peaceful independence movement in the former British Empire, this portrayal is somewhat misleading. In reality, the road to independence was marked by significant tensions and riots. The actual Independence Day was a sombre occasion with no music or dancing permitted, reflecting the underlying struggles. Our work in this room explores these tensions between the concepts of independence, liberation and peace.

We want this space to invite you to think critically about these themes and reflect on what independence and liberation mean on both a collective and personal level. This room houses some of the insights and findings from our research, providing a space for deeper reflection on the complex history of Mauritius.

In the yellow room, we present archival digital prints, showcasing some of the research from our trip to Mauritius. Among these are digital prints created by Rudy, including his ancestors' immigration cards from 1873. This illustrates how the British government utilised technology to document indentured immigrants arriving in Mauritius. Photography, a significant technology of the 19th century, enabled the recording of these immigrants up until 1910.

Bask in the Light of Freedom, archival research in yellow light, Installation View (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

We are particularly interested in exploring the roles of women and children, who are often overlooked in the histories of indentured immigration. This focus aligns with our next project at the Aapravasi Ghat, where we hope to further our research and exhibit in Mauritius next year (2025).

Here, we have an image titled "Cake Sellers," which captures moments where people, despite the oppressive system of labour, managed to collectivise and improve their lives. These acts of resistance and self-improvement are pivotal in understanding the broader narrative of indentured labour.

Cake Sellers, 2024, screenprint, Installation View (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

The Blue Penny Museum Is an art and history museum wholly devoted to Mauritius. It houses some prestigious collections, including the world-renowned Post Office stamps, in a stunning layout that testify to Mauritius' historical and cultural wealth and diversity. The Blue Penny Museum, known for its collection of Post Office stamps, serves as an inspiration for Rudy’s digital prints. Although we only saw a replica while visiting the museum, the original is steeped in history, with only about 20 of these plates ever made, and their theft and subsequent recovery adding to their allure. Rudy’s large scale digital prints combine archival stamps with traditional Indian paisley patterns. Bringing into question these layered histories.

We also have materials from the National Library of Mauritius, depicting colonial Scottish ships like the "Forth" and the "Clyde." These images are from a book titled "Coolie Ships and Sailors," which examines the experiences of indentured workers, often referred to by the pejorative term "coolie." This term, while having negative connotations, was reappropriated by Indian indentured workers to represent their new lives outside of India.

One notable photograph from Glasgow in 1935 shows a crew of indentured workers, post-indentured era, illustrating the continuity of these labour systems. Our exhibit includes archival materials and more contemporary pieces, reflecting on these historical slippages and their implications.

Post Office Not Post Paid, 2024, Digital Print on wood panels, Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

Bask in the Light of Freedom, archival research in yellow light, Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

Our primary partner in Mauritius, the Aapravasi Ghat Trust, publishes monthly materials that provide a glimpse into the lives of indentured immigrants. The steps at Aapravasi Ghat were the first sight for many arriving in Mauritius, marking the beginning of their new lives.

We also have Rudy’s ancestors’ immigration cards from 1873, documenting their journey and employment on sugar plantations. This card includes details such as their names, numbers, the ship they travelled on, and their employer. Notably, women were allowed to work but often confined to domestic roles.

My Ancestors, 2024, Digital Print. Installation view (Photo by Eoin Carey)

For many, including Rudy’s ancestors who travelled from Calcutta, this was their first encounter with the ocean. In Hinduism, crossing the sea, often referred to as the "Black Water," is considered ominous. The journey was arduous, taking three months in the cargo hold of a ship, often with young children. This highlights the immense risks people were willing to take in pursuit of a better life.

As we reflect on these histories, we see how they shape our present narratives and perspectives. The evolving global population and changing narratives offer a more nuanced understanding of people's lives, influencing how we interpret our past and present. This connection is a central theme in our work displayed here.

This might seem a bit of a departure, but here we have some crochet work. I typically use found materials, except for the leaves, which I created at Glasgow Print Studio. This piece reflects the idea that history often repeats itself, exploring the "ecology of time.”

The evolution of our methodology for this show includes frameworks from decolonial practice and crip theory, focusing on alternative economies and different experiences of time. I started crocheting again when I was quite ill, as it was something I could do despite not being able to work in a studio. These crochet pieces have since taken on their own form and are inspired by the rings of a tree, which serve as a natural archive showing periods of growth and periods of harm.

Deep Time Uprising, 2023-2024. Found assorted fibre, laser cut wood. Installation view (Photo by Eoin Carey)

The leaves in Deep Time Uprising are laser-cut and based on photographs from the oldest botanic garden in the Global South, aiming to draw connections and threads throughout the exhibition. This idea of interconnectedness is a key theme. Places like Mauritius, don’t have a “recorded” history before colonialism but our exhibition makes references to ancient records of history making.

The primary methodology for the show is derived from the concept of "creolisation", a term extensively explored by the academic Marina Carter. This concept refers to the blending of diverse cultures into a new, dynamic cultural form. Creolisation is an ongoing process where different human groups merge their histories and imaginations, continually transforming as languages, bodies, and memories intermingle.

This continuous transformation underpins our show’s approach. For instance, this piece by Aurelie, is a beautifully laser-cut book that functions as a cookbook with recipes from various artists. Aurelie is from Mauritius.

Dépi Nou Pié Zamblak, 2023, woodcut, book, wooden bowls, table. Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

Unwrapping Stories, 2024, sugar packet motif, screen print on tissue paper. Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick and Eoin Carey)

Adjacent to this is work by Ines Gradot from Réunion, an island south of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Her primary medium is graphic design, and she was inspired by photographs we took of sugar packets in Mauritius. These are layered screen prints on tissue paper, again highlighting the layering of history.

In this exhibition, sensory experiences play a crucial role. For instance, we have included distinct Mauritian scents like curry leaves, picked from Rudy's uncle’s garden. The aroma of curry leaves is a hallmark of Mauritian cuisine and adds another layer to the experience.

PAPER, GRAPHITE, RUB, REVOLUTION, 2024 paper, graphite, laser cut on wood dimensions variable. Installation view (Photo by Eoin Carey)

PAPER, GRAPHITE, RUB, REVOLUTION, 2024 paper, graphite, laser cut on wood dimensions variable. Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick)

Additionally, there are interactive elements like coins that visitors can use to make rubbings. This practice was very popular during the Victorian era, akin to taking a selfie today. Travellers would make rubbings as souvenirs of their journeys. We have provided different types of graphite for you to try, including larger ones for a varied experience.

I hope this overview ties together all the different aspects of our exhibition, from historical exploration to sensory and interactive experiences. Regarding the next project, this is just the beginning. We wanted to create something engaging and playful to introduce new audiences to these ideas and historical concepts.

In addition, we are collaborating with a local small-batch roastery in Glasgow, UK to create a limited-edition coffee blend titled Passing Isle. wThis blend combines coffee from East Africa and Asia, symbolising the Creolisation process I mentioned earlier. While it’s not an exact academic representation, it provides a general idea and allows people to ‘taste’ history through this fusion. We also have various activities planned for children to engage with, ensuring that everyone finds something interesting.

Furthermore, we’ve included a Victorian-style etched glass window film, popular in Creole Colonial houses. This feature is designed to invite visitors to look out over Merchant City and reflect on the intersection of past and present, encouraging contemplation of the complex histories involved. Nearby, you’ll find the bespoke wooden table and bowls created by Aurelie, which includes additional books and seating. This allows visitors to sit, read, and reflect on the prints and other elements of the exhibition.

Creole House, 2024, victorian-era window etching vinyl on windows, Installation view (Photo by Alan Dimmick and Eoin Carey)

Here is a glossary of terms related to slavery and labour systems used in the transcript:

- Abolition: The action or an act of abolishing a system, practice, or institution, in this context, the abolition of slavery.

- Chattel Slavery: A form of slavery in which the enslaved person is legally considered the personal property (chattel) of the owner.

- Indentured Immigration: A system of labour where individuals worked under contract for a certain period, often in exchange for passage to a new country, and living conditions similar to slavery were common.

- The Great Experiment: A British initiative to demonstrate that free labour (through indenture) was more effective and profitable than slave labour.

- Intercontinental Slavery: Slavery involving the transportation and trade of enslaved people across continents.

- Contract System: A labour system where workers are bound by legal agreements or contracts, which replaced slavery but still had many exploitative elements.

- Nationalised Immigration Service: The governmental control and organisation of immigration processes, which emerged as part of the shift from private to public management of labour migration.

- Colonialism: The policy or practice of acquiring political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.

- Aapravasi Ghat: A historical site in Port Louis, Mauritius, which served as an immigration depot for indentured labourers.

This glossary covers the key terms and concepts mentioned in the transcript related to the history of slavery and indentured labour.

Crip Theory Overview:

Crip Theory is a framework within disability studies and activism that challenges traditional perceptions of disability and normalcy. It intersects with various fields, including queer theory, feminist theory, and critical race theory, to offer a broader critique of how society views and treats disabled people. The term "crip" is a reclaimed abbreviation of "cripple," used by activists and scholars to subvert negative connotations and empower the disabled community.

Key Concepts:

Challenging Normativity: Crip Theory critiques societal norms around what is considered "normal" or "able-bodied." It questions the privileging of able-bodied experiences and highlights how societal structures are often built to exclude or marginalise disabled people.

Intersectionality: It recognises that disability intersects with other identities, such as race, gender, sexuality, and class. This intersectional approach examines how these overlapping identities compound experiences of oppression and discrimination.

Reclaiming Language: The use of "crip" is an act of reclaiming and re-empowering language that has been used derogatorily. It aligns with similar movements within other marginalised groups, such as the LGBTQ+ community's reclaiming of “queer."

Embracing Difference: Crip Theory encourages embracing diverse bodily and mental experiences rather than attempting to "fix" or "cure" them. It values difference and diversity as essential aspects of human experience.

Critique of Medical and Social Models: It critiques the medical model of disability, which focuses on diagnosis and treatment, and the social model, which highlights societal barriers but can still imply a need for normalisation. Crip Theory promotes a more nuanced view that incorporates both individual experiences and broader societal contexts.

Visibility and Representation: The theory advocates for greater visibility and representation of disabled people in all areas of society, including media, art, and policy-making. It challenges the limited and often stereotypical portrayals of disability.

Disability as Identity and Culture: Crip Theory views disability not just as a condition but as a cultural identity with its own communities, histories, and forms of expression. It recognises the rich contributions of disabled people to society and culture.

Radical Inclusivity: It promotes radical inclusivity and accessibility, seeking to create environments where all people, regardless of their physical or mental abilities, can participate fully and equally.

Applications:

Academia: In academic settings, Crip Theory is used to analyse texts, films, and cultural practices, revealing how they perpetuate or challenge ableist norms.

Activism: It informs disability rights activism, advocating for policies and practices that support the autonomy and dignity of disabled individuals.

Art and Culture: Crip Theory is influential in the arts, inspiring works that explore and celebrate disabled identities and experiences.

Significance: Crip Theory is significant because it reshapes how we understand disability, advocating for a more inclusive and equitable society. By challenging entrenched norms and advocating for the acceptance of diverse bodies and minds, Crip Theory contributes to broader social justice movements and enriches our understanding of human diversity.

Further Reading:

Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Are Right About Why You Hate Your Job by Gavin Mueller

Cargo Hold Of Stars: Coolitude by Torabully, Khal (translated by Nancy Naomi)

Coolitude: An Anthology of the Indian Labour Diaspora by Khal Torabully and Marina Carter

Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture by Gaiutra Bahadur

Crip Authorship: Disability as Method by Mara Mills (Editor), Rebecca Sanchez (Editor)

Diego Garcia by Natasha Soobramanien and Luke Williams

Sea of Poppies: Ibis Trilogy Book 1 Paperback by Amitav Ghosh

Links For Further Research:

Aphravitash Ghat Trust, https://aapravasi.govmu.org/aapravasi/

Blue Penny Museum, https://bluepenny.museum/

Intercontinental Slavery Museum, https://ismmauritiusltd.govmu.org/ism/

Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Garden, https://ssrbg.govmu.org/SitePages/Index.aspx

-

-

-

-

-

-

prev nextWhat is a Print?

Jan - Jun 2025 Courses Now Live

The Love of Print: 50 years of GPS

Beginner/Refresher Mezzotint - Book Now!

Support Our Work

Graphic Impact